Treacle-cured Chateaubriand

with beef fat brioche & Marmite butter, smoked brisket-stuffed Portobello mushrooms, fried pickled onion rings, triple-cooked chips, parsley-tarragon-chive emulsion, and red wine sauce.

Setting the Table

Welcome to the first real post on Le Cordon Bong! A quick housekeeping note - there will now be two posts a week:

Post #1 (this post) works through a cookbook recipe, detailing the various components and breaking down what makes the dish great;

Post #2 (out later this week!) repackages that same recipe into a simple(r) and more accessible step-by-step version to make at home, while still retaining the core elements of the dish.

This post is laid out in sections based on different courses of a meal. I’m now going to do that annoying waiter thing of “is this your first time here? Let me explain how our menu works”, instead of assuming you know how to read and figure things out for yourself:

Amuse-bouche - the history and provenance of the dish

Starters - an intro to the fancy Michelin version of the dish I’ll be cooking

Main courses - the actual cooking process

Desserts - thoughts and conclusions on what worked, what didn’t, and most importantly, what tasted good

Petit Fours - footnotes and references

Amuse-Bouche

Kicking off with a steakhouse classic - Chateaubriand for two. According to Larousse [1], it was “probably dedicated to the Vicomte de Chateaubriand (1768-1848) by his chef, Montmireil”. The Vicomte was quite the character who “saw himself as the greatest lover, the greatest writer, and the greatest philosopher of his age”, and would not be out of place in a future season of Bridgerton if anyone at Netflix is reading this.

The term Chateaubriand refers to both the cut of meat (the centre cut of the fillet, aka tenderloin), and the method of preparation (grilling/broiling the meat, and serving with potatoes and sauce - often Béarnaise).

There is also a Chateaubriand sauce named after the same Vicomte (sometimes referred to as crapaudine sauce) which can be served with Chateaubriand steak, but is not considered essential to the dish.

Starters

As many of you know from my previous post, I’m currently working through the Hand & Flowers cookbook by Tom Kerridge, which is where today’s recipe comes from.

To be totally honest, I’m a long time hater of fillet steak. Sure, it’s meltingly tender, but it’s also utterly devoid of flavour, because (1) there is very little fat (as Samin Nosrat says, “fat is flavour”), and (2) it’s the laziest muscle in the cow. Give me a Texas-style smoked brisket any day.

The fillet is often described as the laziest muscle in the cow, as it isn’t utilised much. Consequently, it receives relatively less blood flow, and therefore, less haemoglobin - another important building block of flavour. In contrast, tougher, more heavily-worked muscles such as beef cheeks or oxtail are far more flavourful cuts of meat.

Fillet is also the most expensive cut of steak, which combined with the aforementioned lack of flavour, makes it terrible value, and therefore, the last thing I’d ever order in a restaurant. However, as we’ll see later on, this would be a major life mistake if I ever make it to the Hand & Flowers. Because this dish is an absolute delight.

Main Courses

On the more laborious side of the book, this recipe involves starting 5 days in advance (to brine the brisket), with 8-9 hours of active cooking. Certainly not one for the faint-hearted!

Cured Chateaubriand

I got to practice some amateur home butchery (thanks YouTube) [2] by purchasing a whole fillet instead of getting a Chateaubriand cut. It’s also much better value [3].

The cure is a mix of treacle and Kerridge’s red wine sauce, which is served again with the steak. This recipe really unlocked some insights into why restaurant sauces taste so good - spoiler alert - it’s because one third of the sauce is literally just butter. There’s also a really cool emulsification technique on the sauce that I can’t wait to share in the recipe post later this week.

Ragout-stuffed Portobello mushrooms

The brisket ragout filling for the mushrooms was a ton of work. 5 days of brining, 2 hours in the smoker, and 4 hours braising in the oven. I’m not quite sure why we brine and smoke this unctuous slab of brisket, only to unceremoniously dilute it down with ordinary beef mince later. The leftover beef was great in a toastie with cheese and pickles though.

I also had a lot of fun trying to source caul fat for this recipe. I must have called nearly a dozen butchers and the best I got was a ‘maybe, but I’ll have to ask the manager’. Clearly, I need to step up my Karen game. Thankfully, I finally found Godfreys in Islington, who stock caul fat regularly. A massive thank you - you guys are the best!

Caul fat (aka lace fat, omentum, crépine, fat netting) is a membrane that surrounds the internal organs of some animals, typically pigs. Traditionally used as a natural sausage casing, it’s a gem of an ingredient that allows food to be wrapped up to retain moisture, and boosts flavour as the fat melts away from the membrane.

Beef fat brioche

When I first read this recipe, I thought the brioche was, to put it bluntly, a little extra. Like, aren’t you supposed to have the bread roll at the start of the meal? What’s it doing in the main course? Sorry, Tom.

I also had two more big problems with this recipe. (1) The batch size was too small, so the dough hook was struggling to reach the edges of the mixing bowl; (2) It presumes you know exactly what you’re doing when making a brioche (I did not, having never made brioche before).

So I did some internet sleuthing, and found a brilliant recipe from The Flavor Bender with detailed step-by-step instructions and pictures.

Unfortunately, the first time I tried this recipe, my stand mixer decided to jump off the kitchen counter and shatter its glass mixing bowl into a million pieces. Which is why the photos above feature a makeshift ceramic mixing bowl that I had to hold precariously in place with both hands for the 30+ minutes it took to mix the dough.

I still ended up with some pretty good brioche though, and I would 100%, very highly recommend this recipe to everyone.

Herb emulsion

So, this was a struggle. I hacked together my sous vide and NutriBullet to replicate the ability of a Thermomix to heat and blend simultaneously, which seemed to work. The problems started when I tried to make the emulsion, which is basically a mayonnaise (eggs, oil, salt, acid). Simple, right? Mayo takes like, 2 minutes tops.

The catch was that the herb infusion had changed the structure of the oil (according to a helpful chemist who messaged me on Instagram), making it a lot less stable than usual. The first two attempts quickly disintegrated into an oily mess, and I was so terrified of a third failure that I went extra slow on the third try which took 45 minutes of hand blending, after which my arms were extremely sore.

It would also help if my Kenwood food processor wasn’t so utterly useless (if you see one on eBay or Gumtree in the near future, don’t buy it - it’s probably mine).

Triple-cooked chips

I mean, there’s not much to say here. They’re chips, they’re deep fried, they taste great.

The Finish

The lack of a third hand meant I wasn’t able to take many pictures while juggling 4 very hot pans on the stove and a bunch of things in the oven.

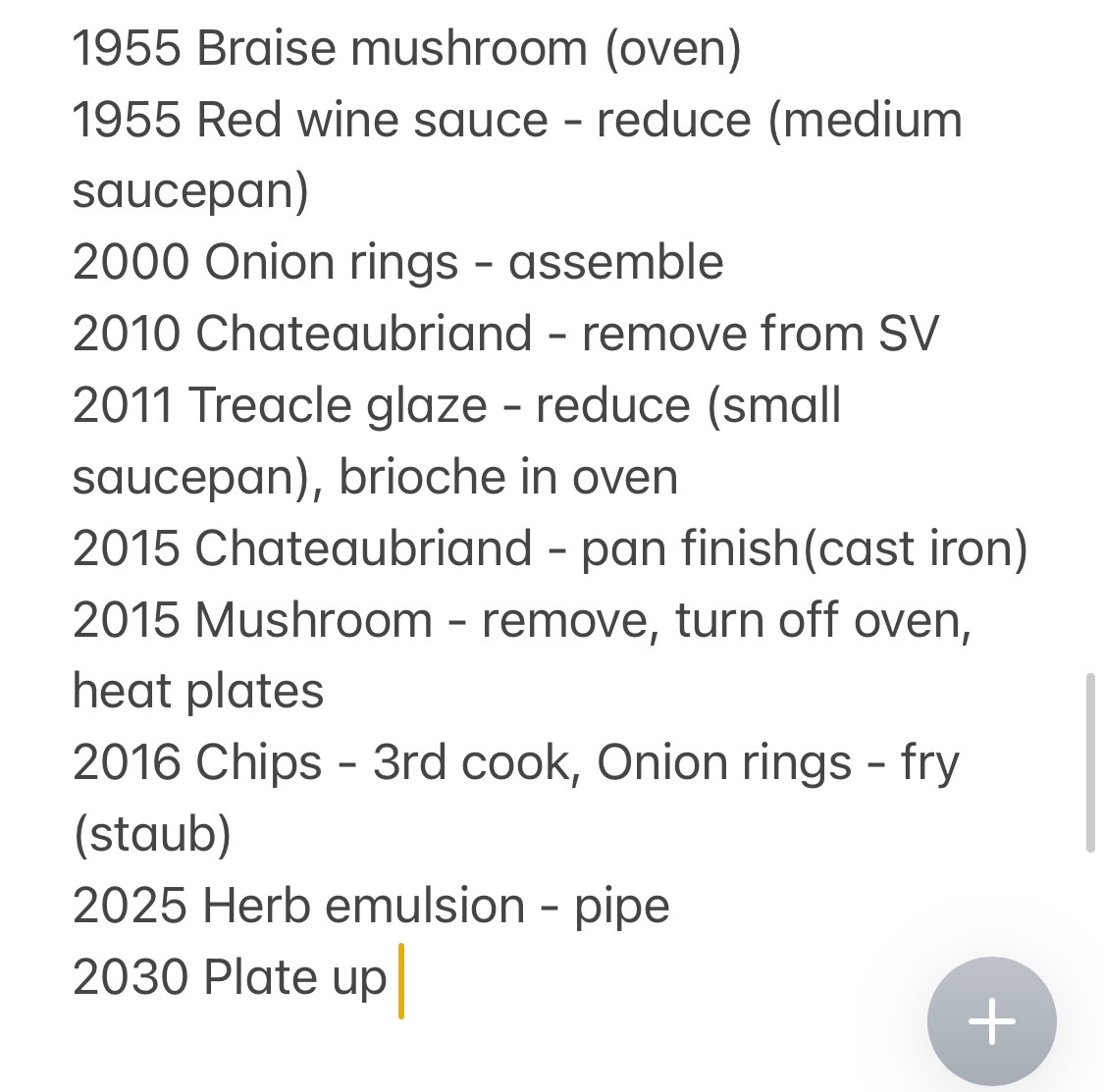

One amazing tip I have when cooking a lot of dishes is to write down overly detailed notes for finishing the cook with exact timings and equipment. I find it infinitely easier when I can just switch off my brain, go full Hermione, and follow instructions - for instance, here are my notes from that evening.

Additionally, the final cook is structured as a 30 minute drill that I can start at any time, because everything starts from cold apart from the Chateaubriand, which can be held warm in the sous vide indefinitely (within reason). I like to do this whenever possible, because it means you can delay your meal time (e.g. if someone is late - you know who you are) without worrying about serving cold food.

Desserts

This was easily the most I’ve cooked in a single day, outside of big dinner parties (remember when those existed?). Was it worth it? ABSOLUTELY.

This dish has single-handedly changed my mind on fillet steak. Perfectly tender, yet full of flavour thanks to the treacle and red wine cure that permeates through the beef, and a sticky glaze of browned butter and caramelised treacle that oozes depth and richness.

The mushrooms were a revelation and could easily be a meal unto themselves. Visually, they just look so unusual that you have no idea what to expect underneath the gleaming brocade of caul fat, which incidentally, is an ingredient that needs to get a lot more love and attention than it does today. #MakeCaulFatGreatAgain

Running through the rest of the meal, the red wine sauce and herb emulsion complimented the steak perfectly, with the parsley and tarragon in the emulsion evoking notes of chimichurri and béarnaise. The chips and pickled onion rings were fried, and therefore tasty. The brioche with Marmite butter was also delicious (duh, it’s brioche), but frankly, unnecessary. Apologies again, Tom. But also thank you for a fantastic meal.

Looking ahead, I’m working on a highly scientific scoring system to rank and compare all recipes that I aim to unveil next week. Also, stay tuned for my Chateaubriand recipe post later this week! I’ll be testing it tonight. Until then, happy cooking!

Petit Fours (aka the footnotes)

[1] Larousse Gastronomique

Larousse is the definitive encyclopedia of French cuisine, first envisioned by the great French chef Prosper Montagné, and published by Éditions Larousse in 1938. The second edition was updated in 2001 by a gastronomic committee chaired by the legend himself, Joël Robuchon (RIP). It’s easily my most-used reference book, and a must-have (or great gift idea!) for any serious home cook. On the pricier side at £50, but it does go on sale from time to time - I picked up my copy for £20 at a TK Maxx several years ago (that’s TJ Maxx for my American readers).

[2] Breaking down a fillet

Below is a good instructional video on butchering a fillet. Note: in the UK, the whole fillet is usually sold without the “chain” cut attached.

[3] The economics of beef

You are almost always going to be better off buying an entire fillet. I buy the vast majority of my meat from Turner & George, who are based in Islington, and deliver nationally in the UK. I paid £78 for a 2kg fillet which works out to £39/kg, whereas a high-quality centre cut fillet will usually go for £50/kg, and up to £70/kg.

Nice work and lucky dinner guests 😋I look forward to seeing the simpler version later this week!

As chemists we have all these little techniques to break emulsions in the lab, but being a good chemist also makes you a great cook because you understand food on a molecular level. I’m currently planning on smoking then braising chateaubriand (between two brisket cuts) and looking for all the hints. Thanks for your website!